15. The Reserves

The Reserves and the Changing Circumstances of Indigenous Peoples in Canada

Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s expedition to Georgian Bay in 1793 provides the first real glimpse as far as written history is concerned of the bands that inhabited the region. Simcoe visited with Great Sail near the mouth of the Holland River and the unfortunate Chief Canise at De Grassi Point. These two bands were part of a larger group under Chief Joseph Snake. These groups ranged from the mouth of the Holland River, up the western coast of Lake Simcoe in the present day Town of Innisfil and probably inland from there. Lake Simcoe was a wonderful source of whitefish, trout and bass. The swamps at the head of Cook’s Bay provided wild rice and abounded with waterfowl. Easy access to the trading post at Toronto was obtained via the Toronto Carrying Place which ran from the mouth of the Humber River on Lake Ontario to Cook’s Bay on Lake Simcoe via the Holland River.

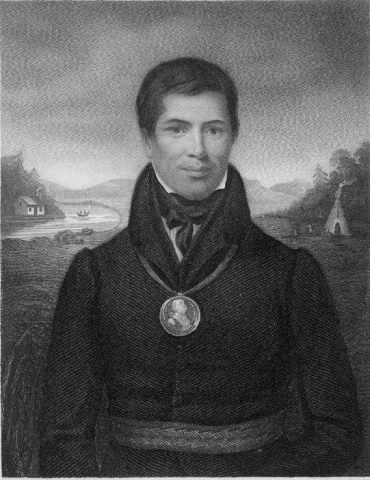

Musquakie (William Yellowhead) was the principal chief of the Lake Simcoe/Georgian Bay/Muskoka area. Musquakie fought on the British side in the American Revolution, though there is some confusion with his father, also known as William Yellowhead. The range of the Musquakie band before the establishment of reserves is unclear though the fact that they settled at the Narrows probably indicates that this area was within their previous range. The Narrows provided a particularly productive fishery. Fishing weirs had been constructed at the site where Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching meet since the Wendat had controlled it. The Musquakie band used the vast forests of Muskoka as their winter hunting grounds. In fact, the name for the District of Muskoka is a corruption of “Musquakie” and its other renditions.

John Assance was the chief of another band that seems to have ranged the southern coast of Georgian Bay. Matchedash Bay was likely the focus of their activities; Assance is one of the signatories of the 1798 Penetanguishene Purchase.

Two other bands were later associated with Musquakie. The Sandy Lake and the Muskoka bands lived in the shield country of Muskoka – the former near Georgian Bay and the latter near modern day Port Carling. Both bands viewed Musquakie as their principal chief.

The strategic nature of the Lake Simcoe area astride one of the most direct routes to the Upper Great Lakes caused their territory to come to the attention of the British authorities in advance of any real demand on the part of European settlers. Early land purchases were all aimed at securing access to the Upper Lakes. The Penetanguishene Treaty of 1798 [Treaty #5, signed on 22 May 1798] was designed to permit the building of a military base on Georgian Bay. The earlier Collins Purchase acquired the two routes to the bay via the Severn River and the “Indian Portage” from the Narrows to Matchedash Bay. The Lake Simcoe Purchase in 1815 [Treaty #16] was at least partially intended to secure the Nottawasaga Bay Route and allow the building of the military road from Kempenfelt Bay to Penetanguishene.

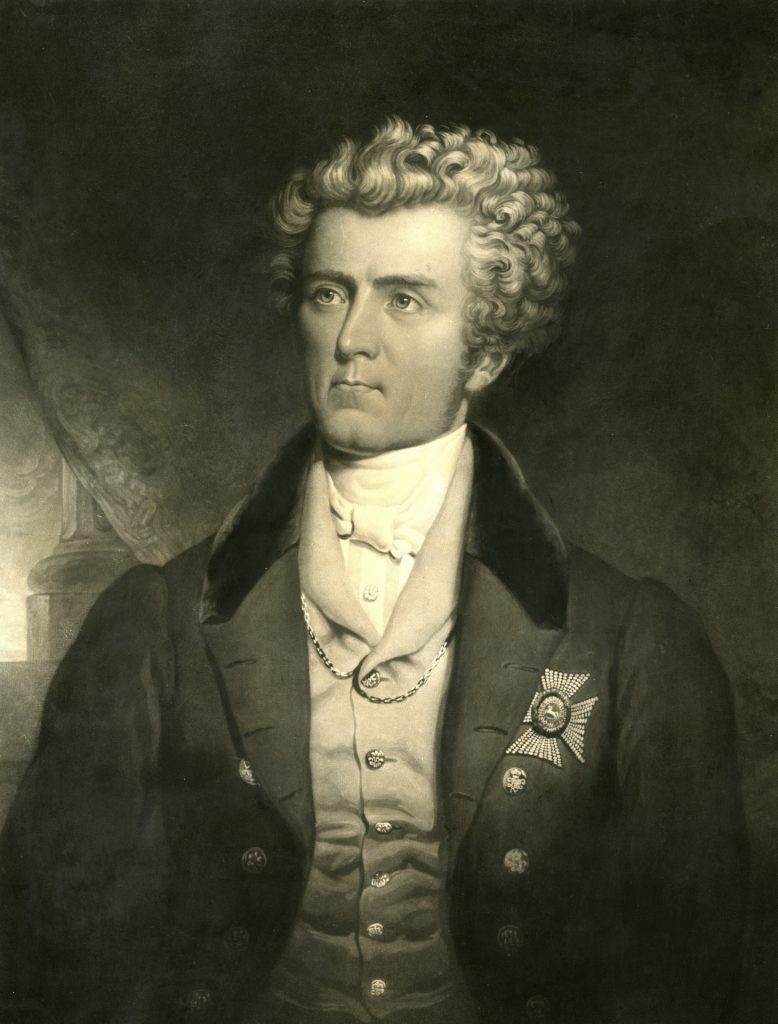

It is not until the Lake Simcoe-Nottawasaga Purchase of 1818 [Treaty #18, signed on 17 October 1818] that settlement is the primary motivation on the part of the authorities. Settlement north of the area outlined by this treaty was slow in coming. However, Sir John Colborne, Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada from 1828 to 1836, decided that First Nations people, having legally ceded title to the land, should be removed to reserves. The reserves established under Colborne were intended to teach aboriginal people to farm like Europeans, enlighten them about Christianity and to “civilize” them in general. The thinking behind this policy was that aboriginal people could only survive if they assimilated to European civilization. Reserves were established throughout the province in which the First Nations would receive “instruction” from missionaries and various Indian agents.

It appears that the plight of aboriginal people at this time was sufficiently desperate that many viewed the relocation favourably. The conversion of First Nations people to Christianity became widespread at this time. Most aboriginal groups, finding themselves in the path of the frontier, seemed to grasp for answers to their plight. Some aboriginal people became missionaries themselves, most notably Kahkewaquonaby (Peter Jones), the great Methodist preacher and Anishinaabe spokesman.

Competition between Christian sects was fierce: Methodists against Anglicans, Roman Catholics against Protestants. This competition is evident in the Lake Simcoe bands. The bands under Joseph Snake and Musquakie were early converts to Methodism while the band under John Assance embraced Catholicism. Assance was related to Kahkewaquonaby and the conversion of his band to Catholicism was a source of pain for the latter. The Muskoka bands, sheltered from the onslaught of “civilization” in the rugged Canadian Shield, maintained their traditional beliefs until the 1860s. Ironically, the acceptance of Christianity by many First Nations people became a source of division within the various communities.

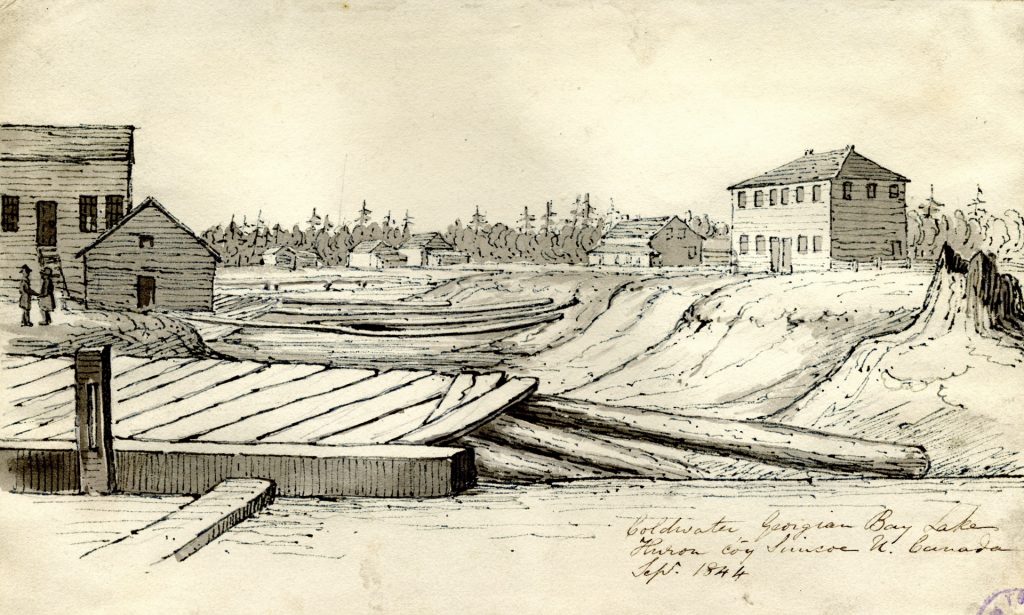

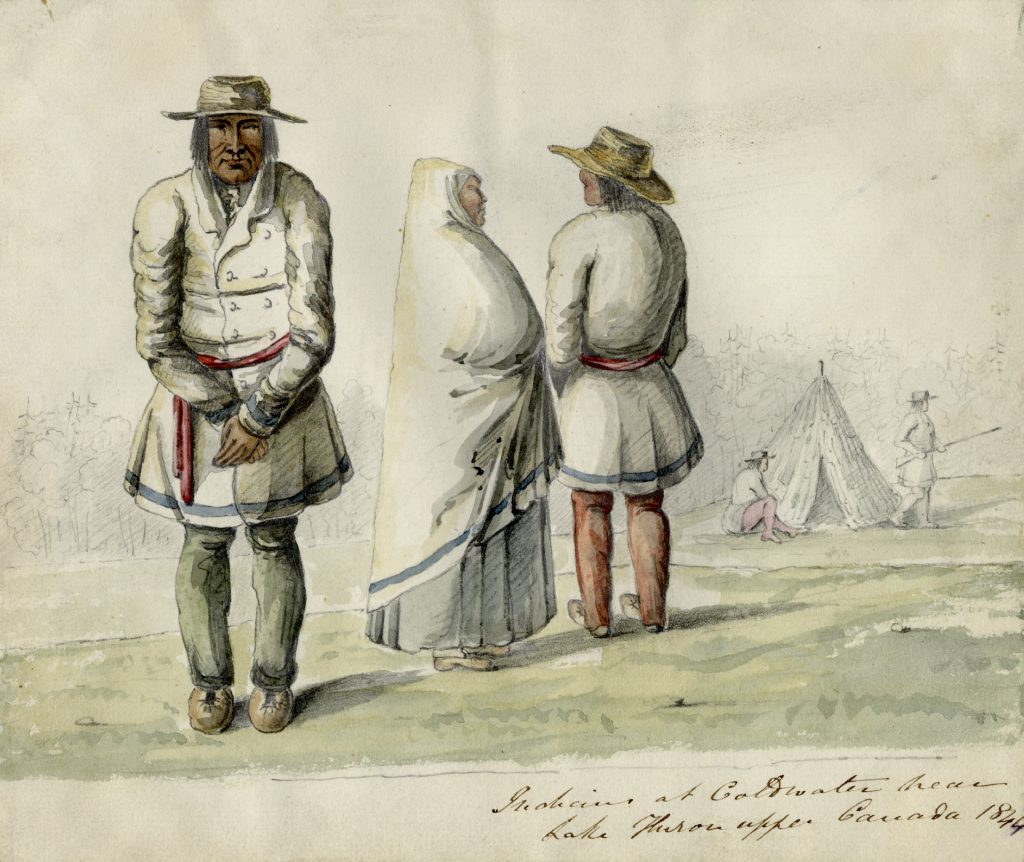

In 1830 the three groups in the Lake Simcoe area (excluding the Muskoka bands who had yet to cede their land) were settled on 9300 acres stretching from the Narrows between Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching and Matchedash Bay at the village of Coldwater.

The band under John Assance settled at Coldwater and Musquakie’s band at the Narrows. The location of the band under Joseph Snake is unclear. Although they seem to be accounted for on the 1834 census, they likely spent much time on the southern shores and islands of Lake Simcoe.

Most of what we know about these people comes from the descriptions of the Coldwater-Narrows Reserve. William Hawkins provides a particularly interesting account of the reserve. Hawkins was Deputy Surveyor of the province and visited the reserve in 1833. The village at the Narrows, according to Hawkins, accommodated forty families and was comprised of sixteen houses, eleven old log shanties, a Methodist meeting room and school and some scattered wigwams. A fine frame house was constructed for Musquakie.

At Coldwater thirteen houses, a saw mill and six log shanties were constructed along with a meeting house/school and a house for the superintendent. In 1833 a gristmill was built in the village to grind the grains grown on the 280 cleared acres of the reserve.

Another band appears in accounts of this time period. The group referred to as the Potaganusus Band under Chief Ashawgashel settled just outside of Coldwater and had 28 acres cleared in 1833. Some accounts perpetuate an old mistake that identifies this group as Potawatomi from Drummond Island. This error has been traced to George Copway, a Methodist preacher and one of the first Anishinaabe chroniclers of Southern Ontario. Copway may have simply misinterpreted “Potaganusus” as meaning Potawatomi. Whether this band was, indeed, from Drummond Island is unclear. The policy of removal of indigenous people to west of the Mississippi River at this time caused many Three Fires bands to seek refuge in Canada.

An Odawa refugee of particular note came from L’Arbres Croches in Michigan. Assiginack (Jean Baptiste Blackbird) was a Roman Catholic lay preacher. Assiginack was a powerful speaker and a rival of Kahkewaquonaby (Peter Jones). He settled at Coldwater in 1832 but left for Manitoulin Island later that decade.

Thomas Anderson, Superintendent at Coldwater, wrote a letter to Lieutenant Governor Colborne in 1835 in which he passionately proclaims the successes of the Coldwater Reserve in giving the Lake Simcoe bands “sufficient Knowledge of the Arts of civilized Life”.

Despite the apparent success of the experiment, the new Lieutenant Governor, Sir Francis Bond Head, resolved to remove First Nations from the destructive influences of civilization. Head seems to have been influenced by the American policy of removal. The Lieutenant-Governor and his agents attempted, with little success, to encourage First Nations bands to settle on Manitoulin Island. Manitoulin was, at that time, beyond the reach of the settlers’ frontier. To encourage migration, Head made the island the centre for the distribution of yearly “presents”. Previous to this change, Penetanguishene was the magnet that attracted First Nations from Upper Canada and the United States.

Many Odawa from the U.S.A. made Manitoulin their new home and Assiginack moved from Coldwater to Wikwemikong in order to join his people at this time.

Few established bands in Southern Ontario, however, accepted the offer of cash for removal. Nevertheless, Head broke up Colborne’s reserves. Many of these reserves found themselves surrounded by land-hungry settlers who lobbied the government for access to the reserves.

Head managed to convince the Coldwater bands to surrender the reserve in 1836. The Lieutenant Governor quoted Musquakie as telling him: “Father, our Children and our Children’s Children, will pray to the Great Spirit to bless your Name for what you have this day done for us…”. However, in a letter dated 26 May 1842, the chiefs of the former Coldwater Reserve complained to the Governor General, Sir Charles Bagot, that Head had “insisted on [their] selling this Land”. The promise of the Coldwater Reserve and other reserves like it in the province had been swept aside for the purpose of acquiring all arable land for settlers. The First Nations in Upper Canada would find themselves living on the rocky margins of the province in the years to come.

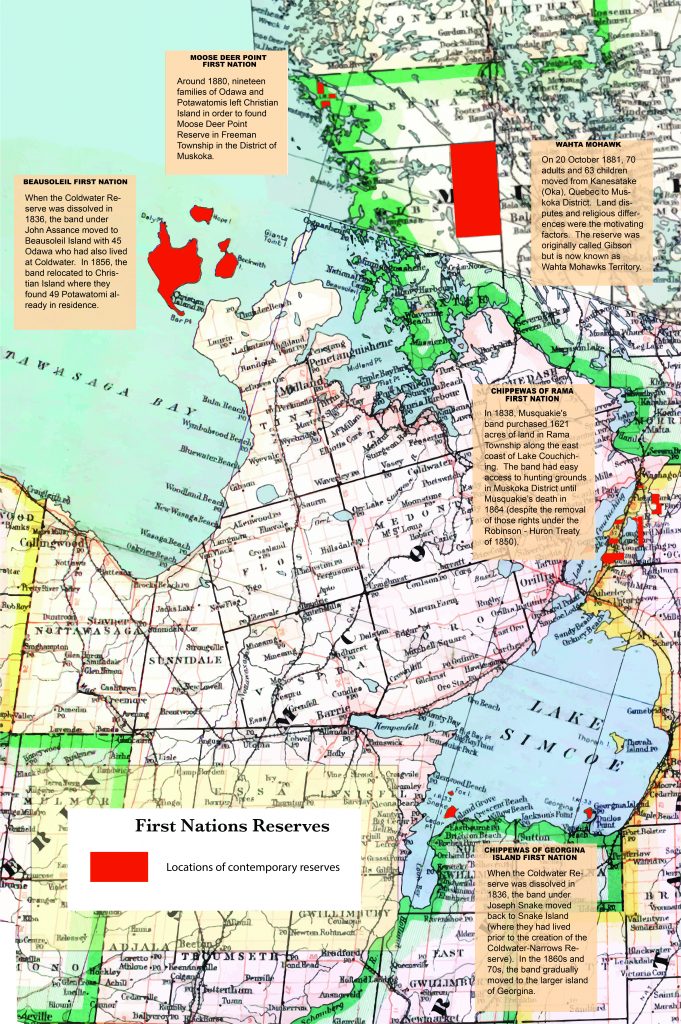

The three bands would go their separate ways. The band under Joseph Snake moved to Snake Island in Lake Simcoe, established a village and cleared about 360 acres for agriculture. However, this was not enough land to sustain the band properly. The population on Snake Island declined in the ensuing decades. In 1847 the reserve had 142 inhabitants. By 1857, the population had dropped to 132 and by 1901 there were only 115 inhabitants. The population was also aging. In 1847, children made up almost half of the population but, by 1901, they numbered barely a quarter of the whole. In the 1860s and 70s, Snake Island was gradually abandoned for the larger Georgina Island. Today, Snake Island is leased to cottagers and the band lives entirely on Georgina.

The Coldwater band had a similar experience when they moved to Beausoleil Island in Georgian Bay in 1842. Agriculture proved almost impossible in the poor soils of the island and a move to Christian Island was necessary in 1856. Just before the move, the band was joined by 45 Odawa from Michigan. This conglomeration was further amended on arrival on Christian Island. It was discovered that a small band of 49 Potawatomis had been resident since about 1835. The Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomis agreed to live together as they had so often in the past. There was, however, some friction between the Traditionalist Potawatomis and the staunch Catholics who comprised the remainder of the community. Pressure was put on the Traditionalists to accept Christianity. Whether this friction had anything to do with the eventual parting of ways that took place in 1876 is unknown. In that year, nineteen families of Potawatomis and Odawa left Christian Island to found their own reserve at Moose Deer Point in Muskoka.

Life has been difficult on Christian Island. Transporting fish or agricultural produce to market has always been a challenge. Penetanguishene is a fair distance from the reserve and the waters of Georgian Bay constitute a barrier especially in the winter. As is the case on many reserves, economic opportunities are few. Many enterprises have been attempted including charcoal production. Tragedies have also visited the small community. In 1918-19, sixty islanders succumbed to influenza and in the early 1970s the ferry connecting the island with the mainland sank with loss of life. Despite all these challenges, the population has grown. The current population of Christian Island is 1,798 with 579 resident on the island (2008).

John Assance led his people to Beausoleil Island but, according to Kahkewaquonaby, he had become “confused and bewildered” by the turn of events that had seen his band go from free and sovereign to dependant wards of the state. In 1847, Assance fell out of his canoe and drowned on his return from Penetanguishene.

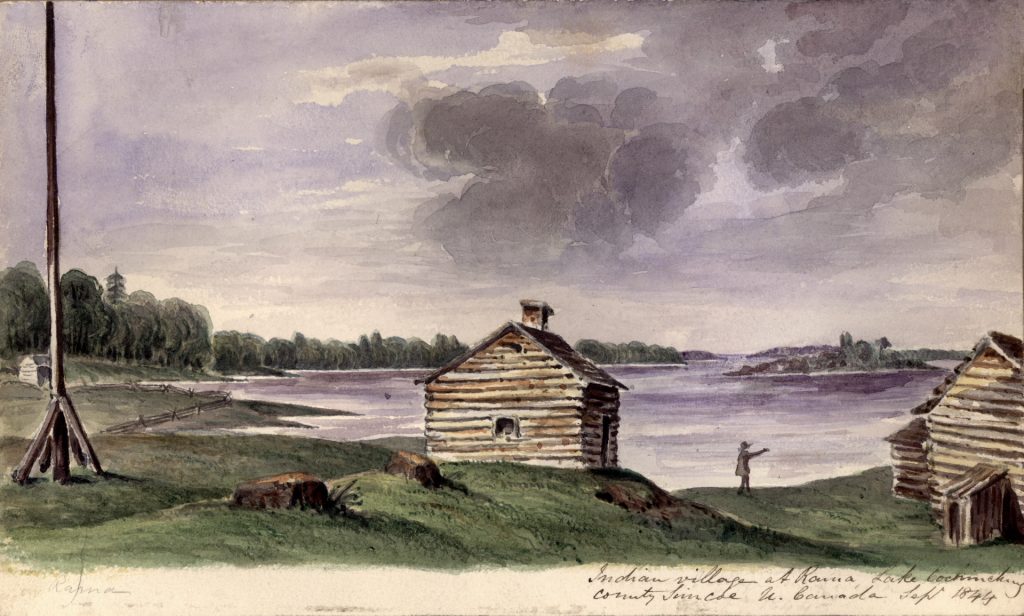

In 1838, Musquakie’s band purchased 1,621 acres of land in Rama Township along the east coast of Lake Couchiching. This land appears to have been passed up by settlers previous to the purchase. Farming was continued but government enthusiasm for teaching First Nations to farm began to wane after 1836. The band was lucky, however, in having continued access to their traditional hunting grounds in Muskoka. Musquakie continued to use the forests surrounding Lake Muskoka as his winter grounds until his death in 1864. Musquakie was 95 (though many claim he was over one hundred) and admired by all in the aboriginal and settler communities. The Robinson-Huron Treaty of 1850 had removed title for the land in Muskoka from the First Nations. Musquakie was not included in discussions preceding the signing of the treaty despite the fact that his hunting grounds were within the territory at issue.

The establishment of a casino on the Rama reserve in 1996 has provided some local opportunity for the Chippewas of Rama (formerly M’Njikaning) First Nation. Casinos are big money makers but there are other partners involved. The operators take a large portion of the revenues as does the provincial government (an estimated 20%). The casino was established on the reserve in order to provide a benefit to the local First Nations. Casino Rama remains one of the largest employers of aboriginal people in Canada, and at the time of opening provided jobs directly and indirectly for 6,000 people in the local aboriginal community.

The two bands in Muskoka were eventually settled on a reserve at Parry Island. The request of the Muskoka band for a reserve of its own near its former territory was conveyed to the government by Musquakie in 1859. Some friction continued between the Sandy Island and Muskoka bands over their joint reserve at Parry Island, the latter desiring a separate reserve. The two groups seem, eventually, to have been reconciled to their joint reserve.

The status of First Nations people and how they were viewed by settler society changed drastically from the beginning of the 19th century to the late 20th. Prior to 1812, First Nations were valued allies. As late as 1838 they were called upon to defend the province when, in the wake of William Lyon Mackenzie’s rebellion, an invasion from the south was feared. But, in reality, their stock had begun to decline after the War of 1812 when their numbers diminished relative to those of the settlers. The terminology used in the various treaties between the government and aboriginal peoples indicates the change in attitude on the side of the government. Early treaties were worded in such a way as to make clear that First Nations bands were sovereign entities. Annuities were assigned to the group to be divided as seemed fitting. By 1850, however, aboriginal people were subjects of the crown and payment for the surrender of the land was assigned to individuals. Furthermore, the crown stipulated who was eligible as a band member. A document dated 1860 from W.R. Bartlett, Indian Superintendent, to James Begahmigabow, chief of the Muskoka band, indicates the new relationship. Bartlett informs Begahmigabow that his recent designation as chief of his band had “met with the approval of the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs” but only until the son of the previous chief grew to the age of majority. Indian Affairs could determine who was chief and who was eligible for band membership.

Government paternalism grew throughout the 19th century. By the early 20th century, Status Indians were not full citizens, could not vote and could not hire a lawyer in order to pursue land claims. Only by moving off the reserve and renouncing Indian status could an aboriginal person become a citizen. The communal nature of First Nations cultures was at odds with that of Canadian society. A reverence for the individual in society is a particular obsession of Anglo-Saxon thought. Much of Canadian history has been a struggle to force this world view on First Nations, French-Canadians, Mennonites, Hutterites, Dukhobors and others.

Assimilation has been the object of government policy at least since 1830. It took over a hundred years for Victorian attitudes of “carrying the white man’s burden” to wane. Today, the past policies of Indian Affairs and the abuses of the residential schools have come to the attention of the general public. Early in the 20th century, the aboriginal population of this country was thought to be doomed as distinct peoples. To quote from Indians of Canada by Diamond Jenness, first published in 1932:

“Doubtless all the tribes will disappear. Some will endure only a few years longer, others, like the Eskimo, may last several centuries. Some will merge steadily with the white race, others will bequeath to future generations only an infinitesimal fraction of their blood. Culturally they have already contributed everything that was valuable for our own civilization beyond what knowledge we may still glean from their histories concerning man’s ceaseless struggle to control his environment.”

This bleak vision does not appear to be taking shape in the early 21st century. Aboriginal populations in Canada are growing rapidly and the impulse to “civilize” and absorb First Nations into the dominant Anglo-Canadian culture has been checked. However, the future of aboriginal peoples in this country is very much unsettled as the incidents at Ipperwash and Oka prove. Are aboriginal people to remain on the margins societally, economically and geographically? This is one of the great issues of our time.

In the first decades of the 21st century, there are signs that the relationship between the Canadian government and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples is changing for the better. Indigenous people have begun to serve notice that unilateral decisions by the Canadian government would no longer be tolerated with the birth of the Idle No More movement in 2012. The movement has involved marches, blockades, and hunger strikes, and is an ongoing action on the part of indigenous groups and their non-indigenous allies. The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was completed in 2015 and a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls began in September 2016. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in 2016:

In the first decades of the 21st century, there are signs that the relationship between the Canadian government and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples is changing for the better. Indigenous people have begun to serve notice that unilateral decisions by the Canadian government would no longer be tolerated with the birth of the Idle No More movement in 2012. The movement has involved marches, blockades, and hunger strikes, and is an ongoing action on the part of indigenous groups and their non-indigenous allies. The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was completed in 2015 and a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls began in September 2016. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in 2016:

“No relationship is more important to our government and to Canada than the one with Indigenous peoples. Today, we reaffirm our government’s commitment to a renewed nation-to-nation relationship between Canada and Indigenous peoples, one based on the recognition of rights, respect, trust, co-operation, and partnership.”

However, resource-related issues continue to cause some to question the commitment of the Federal Government to the true spirit of reconciliation and nation-to-nation co-operation

The aboriginal people of the Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay area have a rich history. As a people they have certainly traveled a rough road since the beginning of the 18th century when they first claimed this land as their own. Like aboriginal people in other parts of the country, survival has never been certain. Nonetheless, their survival as culturally distinct enclaves in the Lake Simcoe-Georgian Bay area has been achieved in spite of powerful pressures from government agencies, churches and Canadian society as a whole.