12. Odawa

The Odawa

The history of the Odawa (Ottawa) has been intermingled and, at times, indistinguishable from that of the Ojibwe. At contact, the Odawa occupied parts of the Bruce Peninsula, the east coast of Georgian Bay and Manitoulin Island. Odawa bands often over-wintered in Wendat villages. Like the Ojibwe, the Odawa were hunter-gatherers and had a loose sense of national identity. The band was the most important political unit, though alliances were often made with neighbouring bands for the purpose of warfare.

French accounts of these people did not, at first, refer to the Odawa as a tribal grouping but catalogued the many bands or collections of bands that existed in the Georgian Bay area. Groups listed in the Jesuit Relations include: Ouachaskesouek, Nigouaouichirinik, Outaouasinagouek, Kichkagoneiak, Ontaanak and Outaouakmigouek.

Like Ojibwe, Odawa refers to an Algonkian language (some would say Odawa is a dialect of Ojibwe) and became a common appellation in the 18th century. Unfortunately, the French often labelled any Algonkian speaking person from the Upper Great Lakes as Odawa. The importance of the Odawa as middlemen in the fur trade beginning in the late 17th century created an association of the name with the activity of fur trading. Thus, other Anishinaabe traders were often referred to as Odawa. The result of this confusion is that it is virtually impossible to distinguish Odawa from Ojibwe and Algonquin in areas where their ranges met. The migration of Odawa people to the lower peninsula of Michigan, as a result of the predations of the Haudenosaunee, created similar confusion between Odawa and Potawatomi bands.

The Odawa were forced to leave their homelands, as were many peoples in the Great Lakes basin, under the pressure of Haudenosaunee attacks. Like many other groups, they spent many years wandering from place to place before settling among the Potawatomi and Ojibwe in present day Michigan.

The Odawa occupied a favoured position in the fur trade of the Upper Great Lakes. After the destruction of Wendake, they established themselves as middlemen in the trade between New France and the Northwest. This position made the Odawa the most ardent allies of the French. The changes brought about by the British take-over of the frontier posts after 1760 were perhaps resented more acutely by the Odawa as a result of their former relationship with the French.

The Odawa occupied a favoured position in the fur trade of the Upper Great Lakes. After the destruction of Wendake, they established themselves as middlemen in the trade between New France and the Northwest. This position made the Odawa the most ardent allies of the French. The changes brought about by the British take-over of the frontier posts after 1760 were perhaps resented more acutely by the Odawa as a result of their former relationship with the French.

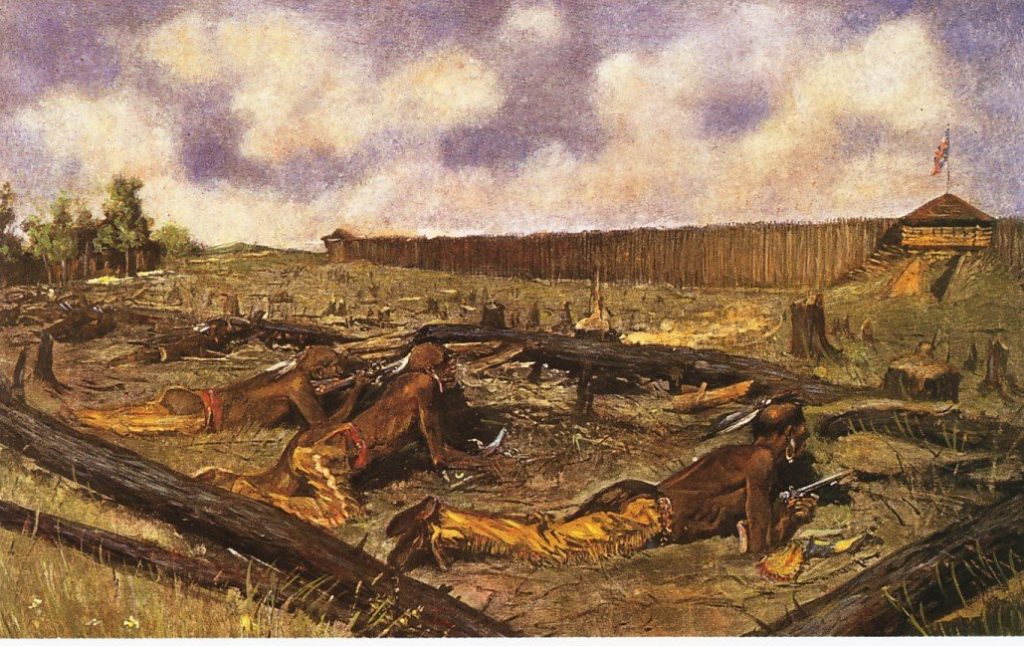

Pontiac’s War in 1763 was an attempt to remove the British from the area or at least to induce them to redress some serious wrongs the people of the area perceived. Pontiac, an Odawa war chief, was by no means an absolute commander of the uprising though he persisted in his bellicosity long after others had made peace. The loose system of leadership among First Nations, as compared to those of Europe, can be seen in the way chiefs signed separate peace agreements regardless of Pontiac’s continued resistance. Although the uprising was an undertaking of many different nations, the resolve of the Ojibwe, Potawatomi and other allies was weaker than that of the Odawa under Pontiac.

Pontiac eventually had no choice but to end hostilities since he had been abandoned even by his own people. The Odawa were forced to accept the presence of the British. For their part, the British became sensitive to the sovereignty of First Nations west of the Alleghenies. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 recognized the western territory as Indian land. The temporary benevolence of Imperial authorities could not, however, counter the resentment of settlers on the frontiers who regarded the Royal Proclamation as an outrage. The American Revolution would alter the stalemate that existed after Pontiac’s Rebellion.

The Odawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi nations eventually formed a confederation known as the Council of the Three Fires, likely as a response to pressures from white settlers after the American Revolution. Many Odawa groups assimilated with neighbouring bands of Ojibwe or Potawatomi.

The history of the three groups south of the Great Lakes was intertwined. The Odawa seem, however, to have predominated on the eastern shores of Lake Michigan where the large settlements around the Grand and Muskegon Rivers and Traverse Bay were established. But villages were also located among the Ojibwe and Potawatomi around Detroit and west of Lake Michigan. After some resistance to the encroachment of settlers on the part of First Nations, the U.S. government began to demand the cession of land in the area at the beginning of the 19th century. By 1836, the Odawa and their allies were almost completely dispossessed of their homelands.

The practice of removal favoured by the U.S. government resulted in the relocation of many Odawa to Kansas and, eventually, Oklahoma. A large number of Odawa, however, resisted this forced migration and moved, instead, to Upper Canada. Some Odawa moved across the Detroit River to join their allies on Walpole Island. Most of the new arrivals to Upper Canada, however, went to their ancient homelands on Manitoulin Island and the shores of Georgian Bay. Catholic Odawa were more likely to seek refuge in Canada and, at the Coldwater Reserve, many refugees were accepted by the band under Chief Assance. The band under Assance were alone among those on the reserve in converting to Catholicism. The bands under Joseph Snake and Chief Yellowhead had converted to Methodism.

Ironically, the arrival of the Odawa refugees in Simcoe County coincided with the beginning of a failed experiment in relocation instituted by Lieutenant Governor Francis Bond Head. Head envisioned moving First Nations from Southern Ontario to the [then] remote and less arable Manitoulin Island. Resistance was fierce among the various communities and few accepted Head’s offers of resettlement. Among the few who did were a small group of Odawa from Coldwater under the leadership of Jean Baptiste Blackbird or Assiginack.

When the band under Chief Assance moved to Beausoleil Island in 1842, however, they were accompanied by 45 Odawa (9 men, 10 women and 26 children). These people were accepted as part of the band as were the 49 Potawatomi that they had discovered on Christian Island when they relocated from Beausoleil in 1856. In 1876, however, 19 families of Odawa and Potawatomi elected to leave the Beausoleil Band in order to found their own reserve at Moose Deer Point in Muskoka.

There are still people on Christian Island today who claim Odawa parentage. Though small in numbers, they remain among the population of First Nations in Simcoe County and the District of Muskoka.